[1] To quote H&R:

"According to the divine command theory, an act is morally required or obligatory just when God commands it, an act is morally wrong just when God forbids it, and an act is morally right or permissible just when God does not forbid it" (143).

The way I interpret this: God creates morality. And while I will also cite some criticisms from the text below in this post, my immediate personal reaction- I don't believe this at all. In fact I find it offensive... I assert that humans can (and do) behave morally even if there's no God (or even if there is a God but they don't believe He exists). Not all humans, no- there's plenty of moral wrong-doing in the world; however I would add that plenty of believers in God have also behaved atrociously throughout history: The Inquisition. The Salem Witch trials. The Crusades. The European settler's/American colonists's near-genocide of Native Americans... I could go on, but the point is made.

I was relieved to find that H&R find problems with the Divine Command Theory as well. Most notably to me, their observation that if the theory were true, then morality would be arbitrary (random, with no reason). Whatever God decided was moral would be the rule, even if it conflicted common sense. Such as if God commanded us to torture criminals, or our enemies.

(This last point demands that I go off on a related tangent): The Judaeo-Christian concept of Hell. Hasn't the majority of modern society decided that torture is wrong? We have the Geneva conventions in warfare; we don't hang or burn or guillotine our criminals anymore; and such recent tactics (at Guantanamo and elsewhere) as water-boarding caused serious ethical debate... And yet, if one takes the Bible literally, God, our creator, is prepared to send us to a "lake of fire" where we will burn forever if we don't follow His commands? Talk about "cruel and unusual punishment"- it's far worse than anything we humans are even capable of. It's just my opinion, of course, though I'm sure many would agree- a literal Hell is absolutely, to borrow a philosophical term, incoherent. How could an omnibenevolent God impose such a punishment?

Okay, back to topic. As H&R point out, a believer in Divine Command Theory could counter that God would never command us to do unreasonable things (nor, one would hope in light of the above, do so Himself). This creates another sort of conflict philosophically, in deciding which comes first- God's commands to be good, or God's being "good" already. (The semantics of all that are, as usual for philosophy, quite involved). To cut to the chase, our text brings up a more coherent way of analysis- an objective (not influenced by personal opinion) view of reality. The two types of objective moral theories featured in the text are consequentialism and deontology.

Consequentialists believe that the results of our actions determine whether they are right or wrong; deontologists counter that it is the type of action itself that makes it right or wrong. Sounds like quibbling, doesn't it? But there are some implications. (Would that mean, as a consequentialist, if I shot a gun at someone with the intent to kill, but missed- that I did no wrong?) While the text goes into some length describing the differences among consequentialists, rather than run too long here, they basically have different ideas about what is intrinsically good and evil. It runs the gamut from hedonism- where pleasure is good and pain is evil, and all other rules don't apply- to people who are so morally uptight and rigid that anything pleasurable is a sin. (I recommend, and most of us would agree, something between those extremes).

Deontology gets shorter shrift in the text- a mention of Immanuel Kant and not much more. Except there's a very informative footnote (19) that gives Kant's three formulations:

(i) Follow rules of action that can be consistently willed to be universal laws. (ii) Treat others as ends in-themselves, and never merely as means-to-an-end. (iii) So act that your will can regard itself at the same time as making universal law through its maxim.

Just off the cuff, I identify more with this deontological view. It sounds more humanist, and far less preoccupied with "Who commanded what" or what is intrinsically good or evil. Maxim (ii) sounds a lot like the Golden Rule, something Jesus or Buddha would say.

I will have to dig in further to be able to comment on some of the denser aspects of this chapter, such as "an infinity of bearers of intrinsic value" or "an (as yet, undiscovered) acceptable (true) purely non-consequentialist moral theory"... H&R's conclusion is that "there is no apparent reason to think that maximal greatness and moral admirability are incompatible" (159). Even without fully understanding all the intricacies, that feels right to me...

[2] To address God's moral perfection from the perspective of a consequentialist moral theory (CMT), we first have to determine the elements of the theory that are most applicable. As a basis, CMT proposes a "supreme moral principle: do that act which, among the acts one can perform, produces (or can be expected to produce) the greatest amount of good minus evil, or in other words, has the best consequences" (H&R 147).

Now, in conjunction with this, H&R begin using a phrase that gets a lot of mileage in this chapter: "bearers of intrinsic values" (good and evil). Although some abstract entities are considered (such as beauty), these bearers are, most realistically, conscious beings- humans, animals, perhaps spirits, and (of course) God.

Although it took me a while to grasp the concept, in a consequentialist universe, all good and/or evil are the result (the consequence- hence the term) of actions. And so apparently, for God to be morally perfect, there would have to be an infinite amount of actions producing good results, borne by an infinite amount of conscious beings. And this makes being "morally perfect" impossible- there would always be one more act to perform. Always one more conscious being to be affected...

The mathematician Georg Cantor is cited in the text, and for those of you mathematically-inclined (or at least -intrigued), he is worth checking out. There's plenty about him and his theories online, but here's the Wikipedia link for the basics: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Cantor (Links to an external site.)

H&R do a sufficient job of conveying how complex Cantor's views on infinity are, so I'll just contribute a few curiosities. In a nutshell, there are an infinity of infinities (a point I remember using in an earlier post). There's an infinity of fractions just between any two real numbers (between 2 and 3 would be 2 1/2, 2 1/4, 2 1/8, etc., forever). Divide any number by 0 and what do you get? Infinity. (That is a simplified answer. Math has never been my strong suit, but I admire those who are adept at it. I highly recommend, for anyone who is interested in mathematics, checking out the "numberphile" channel on YouTube- it will blow your mind...)

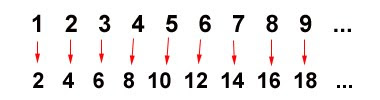

Here's one that sounds impossible: in an infinite set of real numbers, the amount of even numbers (2,4,6,8...) is the same as the amount of even and odd numbers! Don't believe it? The chart below proves it (and it wouldn't matter if the bottom set jumped by hundreds, thousands, etc.) They would still match up, one-to-one, if repeated infinitely... (and this is a much simplified explanation of what Cantor discovered).

The relevance to God's moral perfection? Substitute "even and odd" with "x amount of good and x amount of evil." There would be an infinite amount of both.

icons at the top right corner of the subsection.

icons at the top right corner of the subsection.